The

Governor's Mill, and the Globe Mills, Philadelphia

© Samuel H. Needles, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1884), Vol. 8 , Part 1 pp. 279-299; Part 2 pp. 377-390.

Part 1

No historical sketch has been written of the water-power grain mill built for William Penn in the Northern Liberties, on Cohocksink Creek, where, for one hundred and nine years, it occupied a site afterwards used for the first “Globe” cotton mill. There is also not any connected record of the Globe Mills—the most conspicuous establishment in Kensington for many years, and until about 1850 the largest textile factory in Pennsylvania with possibly one exception. As representative places, the Governor's Mill was a diminutive prototype of monstrous flouring establishments at Minneapolis and in other cities; and the Globe Mill was one of the few factories which, in 1809, despite numerous difficulties, were striving to introduce into the United States the use of cotton machinery. Those members of the Craige, and other families, who were long identified with the latter establishment, having been some years deceased, it seems appropriate that a record of its rise and progress should now be made, before circumstances therewith connected are forgotten or lost.

No mention is made of these two mills in Hazard’s or Day’s Pennsylvania historical collections, and only brief and indirect notices of them in the admirable annals of Messrs. Watson, Westcott, and Ward. Although the first corn and cotton mills of other States are well noticed in Bishop’s ‘History of American Manufactures,’ there is no mention therein of the Governor’s Mill, and very slight reference to the Globe Mills. As the “Roberts Mill” at Germantown dates from about 1683, one was built at Chester for Penn and others in 1699, and Thomas Parsons had one at Frankford in 1695, it is probable the Governor's Mill (built 1700-1701) was the fourth water-power grain mill erected after Penn's arrival. All the machinery for it, of very rude description, was imported from England, as was also done for its predecessors; and there is reason to believe that English bricks were used for certain parts of the building. Power was derived from Cohocksink Creek, formerly called Coxon, Cookson, and even Mill Creek—the race descending from a pond covering almost three acres at the junction of the western branch, which entered said pond near the present northeast corner of Sixth and Thompson Streets.

The triangular sheet of water was bounded on the south by a lane, now Thompson Street, east by “Old York Road,” now Fifth Street; and the third irregular line stretched from the corner above named to where the creek entered, about the present junction of Fifth Street and Timber Lane, now Master Street. The main stream, rising near the locality now known as Twenty-Fifth and Clearfield Streets, turned from its east course just below the intersection of Fifth Street with Germantown Road, and ran south into the said mill-pond. On Foley’s map of 1794, the ground between the creek and race is depicted as swampy, and it is known to have been frequently inundated. “Green Mill” is the name given to this mill on said map, which will be hereinafter explained. Dimensions of the one-and-a-half story building were forty by fifty-six feet, walls very thick and of extra large stones, windows few and small; and the double-pitched shingle roof had heavy projecting eaves.

The earliest facts respecting the Governor’s Mill are found in the “Penn and Logan Correspondence,” where, however, they are neither frequent nor satisfactory; and no mention is made therein of mill property transfer by William Penn or his agents. When returning to England, after his second visit, Penn, writing from the ship Dolmahoy, in the Delaware, November 3, 1701, 1 says: “Get my two mills finished [one was the Schuylkill Mill, yet to be noticed] and make the most of these for my profit, but let not John Marsh put me to any great expense.” The Governor’s Mill, though it was certainly a great accommodation to many of the inhabitants of the new town and the Liberties, did not prove a profitable investment to the owner. Part of the difficulties arose from the want, for a long time, of proper roads and bridges in its vicinity. Pegg's Run, whose course was along what is now Willow Street, caused an extensive district of marsh and meadow as far north as the junction of Front Street and Germantown Road; and on the south, similar low lands reached to and even below Callowhill Street. Watson refers to this difficulty as follows:—

“The great mill, for its day, was the Governor’s Mill, a low structure on the location of the present [1830] Craige's factory. Great was the difficulty then of going to it, they having to traverse the morass of Cohoquinaque (since Pegg’s Run and marsh), on the northern bank of which the Indians were still hutted. Thence they had to wade through the Cohocsinc Creek beyond it. Wheel carriages were out of the question, but boats or canoes either ascended the Cohocsinc, then a navigable stream for such, or horses bore the grain or meal on their backs.” 2

Records exist of horses and their riders sinking and being lost in these marshes and quicksands, between Front and Third Streets. Watson again says (1: 478): “In the year 1713, the Grand Jury, upon an inspection of the state of the causeway and bridge over the Cohocsinc, on the road leading to the Governor's Mill, where is now [1830] Craige's manufactory, recommend that a tax of one pence per pound be laid to repair the road at the new bridge by the Governor’s Mill and for other purposes.”

Above Second Street, northwest from Germantown Road, and towards the mill pond, the land became considerably elevated; and, excepting the space between the creek and the mill-race, the locality was, even up to 1820, one of much sylvan beauty, sometimes made wild enough, however, when, after heavy rains, the widely swelled creek rushed along over its muddy bed like a mountain torrent. The banks and vicinity of the mill-pond were for many years a favorite resort. Miss Sarah Eve, whose interesting diary is published in PMHB (Vol. 5: 198), tells how she and a friend wandered around its shores and gathered wild flowers.

The first difficulties from freshets and other causes at this “Town Mill,” as Logan sometimes calls it, are portrayed in his letter to Penn of 7th of 3d month, 1702, 3 wherein he makes a general complaint about this and the Schuylkill Mill. “Those unhappy expensive mills have cost since at least £200 4 in our money, besides several other accounts on them. They both go these ten days past. The town mill (though before £150 had been thrown away upon her through miller’s weakness and C. Empson’s contrivance) does exceedingly well, and of a small one is equal to any in the province. I turned that old fool out as soon as thou wast gone, and put her into good and expeditious hands, who at the opening of frost would set her agoing, had not the want of stones delayed; and the dam afterwards breaking with a freshet prevented. A job that I was asked £100 by the miller who lately came from England (Warwick's Real) to repair, but got it done for £10. The walls in the frost were all ready to tumble down, which we were forced to underpin five feet deeper, the most troublesome piece of work we had about her. There is nothing done in all this, nor is there anything of moment, without Edward Shippen's and Griffith Owen's advice, where his is proper.”

Logan writes to Penn, under date of 13th of 6 month, 1702, 5 with severe complaint of the aforementioned J. Marsh: “The town mill does well, but has little custom; Schuylkill Mill went ten days in the spring, but [I am] holding my hand in paying J. Marsh's bills, which he would continue to draw on me for his maintenance, notwithstanding he had the profits of the mill, went privately away from her towards New England, without any notice, and now is skulking about in that province; the mill in the mean time is running to ruin, for nobody will take to her, she is such a scandalous piece of work, should we give her for nothing. 6 Pray remember to send over a small pair of cullen stones for this of the town.”

Other mill difficulties are mentioned in Logan’s letter of 2d of 8th month, 1702. 7 “The town mill goes well, but will not yield much profit, though the cost above £400, 8 without a pair of black stones or cullens, which I wrote for before. The miller next week leaves for that on Naaman’s Creek; we have not yet got another.” . . . There must have been additional troubles, for Penn writes anxiously to Logan from London, 1st of 2d month, 1703: 9 “Take care of my mills.” In a letter, about 6 month, 1703, complaining, of his financial difficulties and the opposition of some persons, Penn writes: 10 “Make this matter as easy as may be; the land granted from the mill at town's end would have done the business... I can satisfy thee I have writ to none anything that can give them the least occasion against thee.”

The occult expressions probably relate to the sale in 1701-2, and 3, of portions of the “bank lot” of Lætitia (Penn) Aubrey—which lot extended from Front to Second Street, and 172 feet southward from Market Street—the necessity for which seems to have been a sore point with her father. Thomas Masters had already built his “stately house” at the southeast corner of Front and Market Streets, had purchased a lot forty-six by seventy-four feet for £290, and an annual rent of two shillings, on the south side of Market above Front Street, others had also purchased lots, and Logan had signed his own name to Thomas Masters’ deed, 11 though the attorneyship of himself and Edward Penington, deceased, was duly therein recited. 12

The next Logan letter which refers to the Governor’s Mill is dated 5th month, 11th, 1707-8, 13 when he writes bitterly: “Our mill proves the unhappiest thing of the kind, that ever man, I think, was engaged in. If ill luck can attend any place more than another it may claim a charter for it. I wish it were sold.” 14 This unfortunate condition continued nearly six years, and finally the mill was sacrificed; and it probably would have remained an incumbrance much longer, but for the invention of a woman, as will hereinafter appear.

Thomas Masters, who came from Bermuda in 1687, was one of the wealthiest of early Philadelphians. Besides various houses and lots in the built portion of the city, be acquired at sundry times over 600 acres in the Northern Liberties, mainly north and west from Cohocksink Creek, and extending from near the Delaware River beyond what is now Broad Street. He was mayor of Philadelphia in 1708, and Provincial Councillor from 1720 to 1723. Watson, under the caption “Quacks” 15 has the following curious story, which may explain the subsequent purchase of the Governor's Mill:

“We have on record some ‘fond dreams of hope’ of good Mrs. Sybilla Masters (wife of Thomas) who went out to England in 1711-12 to make her fortune abroad by the patent and sale of her ‘Tuscarora Rice,’ so called. It was her preparation from our Indian corn, made into something like our hominy, and which she strongly recommended as a food peculiarly adapted for the relief and recovery of consumptive and sickly persons. After she had procured the patent, her husband set up a water mill and suitable works near Philadelphia, to make it in quantities for sale.”

English patent No 401, the first to any person in the American colonies, was granted November 25th, 1715, “to Thomas Masters, of Pensilvania, Planter, his Exectrs, Admrs, and Assignes, of the sole Use and Benefit of A New Invencon found out by Sybilla, 16 his wife, for Cleaning and Curing the Indian Corn Growing in the severall Colonies in America within England, Wales, and Town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, and the Colonies in America.”

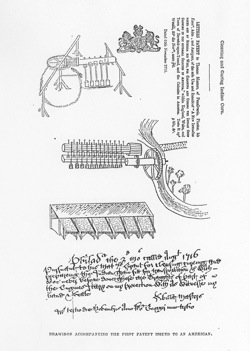

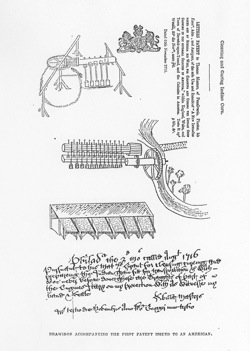

The arrangement was simply two series of stamps in mortars, to be driven by horse or water-power, acting through wooden cog-wheels on a long cylinder, the latter having projections to trip stamps or mallets. There were also included a number of inclined trays. At the foot of the rude drawing of the machine there is the following in old English script, apparently an additional claim or afterthought:—

Philada, the 2d 6mo called August 1716.

Pursuant to his Mjsties Grant for the using tryeing and preparing the Indian Grain fitt for transportation & Which was never before done these are Example of part of the Engines I [obscure] on my protection With the Witnesse my hand and Seale

SIBILLA MASTERS.

In tertio die Novembris Anno MDCCXVI Georgij anno tertio. 17

By patent deed, dated December 25, 1714, under the proprietor’s seal, Richard Hill, Isaac Norris, and James Logan, the duly constituted commissioners of William Penn, conveyed to Thomas Masters two tracts called “the mill land,” respectively 16 and 8 acres, the former tract including the mill-pond, dam and race, the Governor’s Mill and all its appurtenances, mill lot, etc.; and the other tract was stated to be contiguous “to his [T. Masters] other lands,” and probably abutted on the 18 acres above mentioned. It is, however, not possible now to trace the bounds as then given. The price paid for the whole was £250, Pennsylvania money, besides one English sixpence piece annual quit rent, being about $912.50, present currency. It is recited in the deed that the conveyance was made with the consent of the eight holders of the mortgage on the province for £6600 sterling, given October 8, 1708, 18 but it is not stated that the property conveyed was subject to that incumbrance, nor was provision made for its release. 19 The following, is a copy of this interesting document, now for the first time made public:—

PATENT TO THOMAS MASTERS FOR THE MILL LAND.

William Penn true and absolute Proprietor and Governor in Chief of the Province of Pennsylvania and territories thereunto belonging To all whom these presents shall come sends Greeting. Know ye that in consideration of the sum of two hundred and fifty pounds of lawful money of the sd Province to my use paid by Thomas Masters of the City of Philadelphia Mercht the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged & the sd Thomas Masters his Heirs Executors & administ and every of them is by these presents forever acquitted and discharged of & from the same & every part thereof I have given granted enfeoffed released & confirmed and by these presents for me my Heirs & Successors do give grant enfeoff release and confirm unto the sd Thomas Masters and in the first year of the reign of King George over Great Britain & c.

Richard Hill Isaac Norris James Logan

Recorded ye 26th of September 1719, in Patent Book A. Vol. 5 page 383. Copied in Exemplification Record No 2, page 219, in Recorder of Deeds’ office, Philada.

Thomas Masters died in 1723, “seized” its two of the principal brief’s of title now express it, “of about 600 acres in the Northern Liberties, Philadelphia.” Of all title previous to 1723, the said briefs are silent. His will (Deed book D. page 380), dated Dec. 4th 1723, was proved January 16th 1723 O.S. In this will is the following clause:-

“And I give and devise unto my said son William Masters and to his Heirs and Assigns forever, all that my Messuage or Tenement, Plantation and Lands on the South West side of Germantown Road aforesaid in the said Northern Liberties, beginning at the Intersection of John Harvey’s line, and from thence extending with the same Road unto the Land claimed by Benjamin Fairman, and from the Road westward and southward to the full extent of my Boundaries so as to include my whole Right in Lands there. Together with the Mill, Mill-house, Buildings, Improvements and Appurtenances to the same Messuage and Plantation belonging… and all utensils belonging to husbandry or ye mill aforesaid.” He also requests that his cousin Richard Tyson should have, for a coopershop, a piece from certain tracts of land devised to his sons William and Thomas jointly-said piece to be “somewhere near the Mill.”

[It will be well to pause here to consider a singular fact. Among numerous conveyances of tracts large and small in the Northern Liberties to Thomas Masters, no plain mention appears to be made in any of them of the mill, mill-pond, or race as constituting neighboring property or boundaries, except where Mary Fairman, widow of Benjamin, by deed September 8th 1719 (Deed book F, page 76) conveyed 256 acres to Thomas Masters, and among other bounds it is recited, that the tract is “bounded on the west by lands of John Staceys and the Governor’s Mill.” This silence is the more remarkable, since the mill and water power were of considerable importance to the district. In a deed of confirmation from Nicholas Moore, Jr., and sister to Thomas Masters, dated April 23, 1713, 20 it is stated that 280 acres-200 in one tract and 80 in another - had been conveyed by Dr. Griffith Owen, “by deed acknowledged in the Court of Common Pleas, September 7, 1704,” to Thomas Masters (the original record cannot now be found), “which said premises were formerly in the tenure of the said Nicholas More;” but there is no mention in said confirmatory deed of mill-pond, dam, or mill property. The 80 acres were deeded to Dr. More by Thomas Holme, Sept. 5th, 1685. 21 Further, although in the printed explanation of the map of 1750—as republished in 1846—the 16 acres, forming part of the “Mill Land” aforesaid, are mentioned as purchased by Thomas Masters “from the proprietors” (an incorrect plurality), and though the courses thereof are the same as in the patent deed for the mill land as hereinbefore given, there is no mention in said reprint of any mill-property, except that one of the courses of the 16-acre tract was “W. S. W., 16 perches to a mill race;” and another boundary ran “on the several courses of the race 75 perches.”]

Mr. Townsend Ward (PMHB., Vol. 4) remarks:

“On the map of 1750 there is placed between the branches of the [Cohocksink] stream spoken of, a property marked “Masters,” and another one similarly marked to the east of it. These are the same that Varlé, on his map, marks as “Penn’s.” The tract of 200 acres, already mentioned as conveyed by Dr. Griffith Owen to Thomas Masters, was called “Green Spring,” 22 and was long the summer home of the latter, and afterwards of his son William Masters. This name will explain the appellation “Green Mill” on Foley’s map of 1794.

Thomas Masters, Jr., died in December, 1740, without issue, and by will dated December 4, 1740, left nearly all his real estate to his brother William Masters. The latter married, at Christ Church, August 31, 1754, Mary Lawrence, who had either inherited or had built the mansion on the south side of Market below Sixth Street, occupied for two years as headquarters by Sir William Howe, and upon whose site Robert Morris afterwards erected the house where President Washington resided. William Masters was, for many years, one of the principal citizens of Philadelphia, and held several honorable public offices. 23 He resided partly at his “bank house” southeast corner of Market and Front Streets, but chiefly, as Keith says, 24 “at the plantation of Green Spring, operating the Globe Mill on Cohocksink Creek;” but, as here inafter shown, he probably rented the mill or mills to other parties.

All the woodwork of the mill was destroyed by fire, as per an item in the Pennsylvania Gazette of March 20th, 1740.

“Tuesday last [March 18th] the Mill commonly called the Governor’s Mill, near this Town, took Fire (as it’s thought by the Wadding of Guns fired at Wild Pidgeons)—and was burnt down to the Ground.” The reason given was not improbable, since the country around was in an almost original state of wildness, and the shingle roof must have been then in it crumbling condition, inviting ignition. William Masters put a new ground floor, attic floor, roof, and windows upon the solid walls that remained, but circumstances about to be mentioned indicate that no grain grinding machinery was placed in the mill. William Masters died November 24, 1760, and his will 25 gives to his wife Mary a life interest in the aforesaid 26 “bank house” and his plantation of “Green Spring,” or so much of the latter as was not leased. The whole of his extensive real estate was to be equally divided among his daughters Mary, Sarah, and Rachel (the last named afterwards died in childhood); and the widow was also to receive an annuity of £350 from the rents of the estate.

The first known change of the property in question from a corn mill is shown by an advertisement which appeared in the Pennnsylvania Gazette frequently during the early part of the year 1760. 27 The announcement has the representation of a peculiar bottle and the proprietary seal, and, in part, reads as follows:

“Whereas Benjamin Jackson, Mustard and Chocolate Maker, late of London, now of Lætitia Court, near the lower end of the Jersey Market in Philadelphia, finding that, by his former method of working those articles he was unable to supply all his customers, he therefore takes the liberty of thus informing the Publick, that he has now at a very considerable expense, erected machines proper for those businesses, at the mill in, the Northern Liberties of this city, formerly known by the name of the Governor's, alias Globe Mill, where they all go by water, altho’ he sells them only at his Mustard and Chocolate Store, in Lætitia Court, as usual.”

Very soon after, perhaps in the year 1760, a partnership was formed between a Captain Crathorne and Jackson, to continue this business at the Globe Mill. 28 Jackson's interest was purchased by Crathorne in 1765; and the latter dying in 1767, his widow, after having removed store and dwelling to the corner of Market Street and Lætitia Court, advertised that she would continue “the manufacture of the articles of mustard and chocolate, to those incomparable mustard and chocolate works at the Globe Mill, on Germantown Road.” She died in 1778.

Until 1839, there stood, fronting lengthwise upon Germantown Road and a few feet south of the present position of the stack of the Globe Mills, a small 1-1/2 story building. Its stone walls were over two feet in thickness, while the chimney and some other parts were built of English bricks, evidently imported very early, for such practice did not continue after 1720. Tradition among the Craige Family and others says this was originally a grist mill; some have always heard that it was a snuff mill just before the Revolution. Both traditions may be correct. Although there is no distinct mention thereof, it is possible the building was erected by James Logan and his advisers as accessory to the Governor's Mill. 29 The ancient English bricks partly composing it seem to favor this idea; about these there is no error, for Mr. Henry Einwechter informed me that he aided his father to build them into the stack of the Globe Mills.

Another view is, that since Thomas Masters obtained possession in 1714, and had the intention of making “Tuscarora Rice,” be may have built this small mill to develop that business. As already quoted, Watson expressly says that he “set up a water-mill and suitable works near Philadelphia to make it in quantities for sale.” If this were so, it was because he desired not to disarrange the machinery of the Governor’s Mill. That there were two mills at the time of Thomas Masters’ death seems probable from an expression in his will, “Together with the mill-house, building, etc.”

It is almost a certainty that this small house formed part of the mustard works of Crathorne & Jackson, even if not previously a snuff mill. Such a building, with or without power, could have been, and probably was, used as part of the block calico printing works of Jno. Hewson, yet to be mentioned as located at the Globe Mill shortly after the year 1800. As to the power used, we can only codjecture. The topography and elevation were such that a branch from the race-the location of which will be hereinafter described —could have supplied a breast wheel of same diameter as the overshot wheel of the Governor’s Mill, or an overshot wheel of about 8 feet less diameter. There was, doubtless, at first, ample water for the amount of work that could be done in this little place; but many small mills were worked by single horsepower at that time.

Mrs. Mary Masters continued to reside during the remainder of her life chiefly at “Green Spring;” and in 1771 there appeared the notice of a petition by citizens, that “a public road leading from the upper end of Fourth Street to the Widow Masters’ land, near her mill dam, should be opened into the Germantown Road,” which was granted.

On May 21, 1772, Mary, daughter of William Masters and Mary, his wife, married Richard Penn, 30 grandson of William Penn; and in 1774 (various minor conveyances, agreements about annuities, etc., having in the interim been made among the parties in interest) it become needful, for important reasons, to define with certainty the boundaries and locations of the various properties then jointly belonging to Mary Masters Penn and Sarah Masters, and to make a legal division. Lewis, in Original Land Titles in Pennsylvania, page 166, says: “The original survey of the Liberty Land was lost at a very early date 31 and in 1703 a warrant issued by virtue of which the whole was resurveyed as far as practicable, according to the original lines.” 32 This must have altered the courses and bounds as recorded in many first patents and deeds; and even the revised boundaries were now, in large degree, obliterated, owing to the marks being chiefly wooden posts and notched trees. The division was, however, the more imperative, because an act of Assembly of 1705 was in force, which, though very vaaue, might through neglect, cause much confusion and dispute. “Seven years’ quiet possession of lands within the Province, which were first entered on upon equitable right, shall forever give an unquestioned title to the same as against all during the estate whereof they are or shall be possessed.” 33

On December 12, 1774, at the petition of Richard Penn, Mary Masters Penn and Sarah Masters, the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia ordered a partition of the real estate of William Masters, deceased, equally between his two surviving daughters, which division, and settlement of bounds, was made by a sheriff's jury, and returned under date of March 1, 1775. 34 Herein (or perhaps more clearly shown in “Briefs of Titles,” pamphlets, Vol. 2. in library of His. Soc. of Penna., in the matter of “Lands held by trustees of Mrs. Mary Masters Ricketts,” a daughter by the subsequent marriage of Sarah Masters, page x.), certain tracts, i.e., No. 10 of 26 acres, and No. 12 of 4 acres and 80 perches, were, inter alia (seventeen in all), adjudged to Sarah Masters; but, as also in the more ancient instances already mentioned, neither mill nor water power was recited in said partition.

[As nearly as I can trace the boundaries, it was No. 10, only two acres larger than the two tracts in the deed for the “Mill land” to Thomas Masters, or, perhaps Nos. 10 and 12, which together included the mill land, mill buildings, and water power, afterwards forming the Globe Cotton Mill property. With the latter there were various lots, the one where the mill was located extending north as far as the junction of Third Street with Germantown Avenue-Franklin Street, afterwards Girard Avenue, not being then opened. 35 These remarks, are of course, somewhat anticipatory.]

Miss Masters, after the adjudication of her real estate, continued renting the Globe Mill to parties for purposes similar to the one already mentioned; but for many years, records on the subject, if they exist, are not accessible. The Pennsylvania Gttzette of January 6, 1790, however, has an advertisement stating that mustard and chocolate manufacturing, was continued by W. Norton & Co., and M. Norton & Co., “who give thirty-two shillings per bushel for good, clean, Mustard Seed, and in proportion for smaller quantities, at the store of the deceased [most probably the Widow Crathorne, as the place is the same], now of the subscriber, on the south side of Market Street, about half way between Front and Second Streets, where orders from town or country are carefully attended to by John Haworth.”

The Philadelphia journals of 1790-2 show active competition in the spice business; and probably Mr. Haworth did not continue it long. In 1792 or ‘93, James Davenport put in operation at the Globe Mills, machinery patented by him in 1791 for spinning and weaving flax, hemp and tow, by water power. The mill was visited by President Washington and several members of Congress in 1793. Davenport died a few years thereafter, and the machinery was sold in 1798. 36

In 1779, John Hewson, a revolutionary soldier, had established linen printing works, using hand printing blocks, at what was afterwards Dyottville, and now the suburb Richmond, receiving £200 aid from the Assembly in 1789. Mrs. Washington frequently wore calico dresses, woven in Philadelphia and printed at this establishment. Bishop mentions (History of American Manufactures, Vol. 2: 100), that John Hewson’s print works were removed to the Globe Mills, but does not state in what year. They were there in 1803. 37

Sarah Masters visited England, Scotland and Ireland in 1795, and while there, married Turner Camac, a scion of one of the oldest Irish families, originally of Spanish extraction; he possessed several handsome landed estates, and a valuable copper mine. Miss Masters shortly before her marriage obtained from John Davagne £5000 on mortgage upon her real estate in the Northern Liberties. Some years after their marriage, when Mr. and Mrs. Camac came to reside in the large old house on the west side of Third above Union Street, Philadelphia, and Mr. Devagne having in the mean time died, it became a question how to avoid inconvenience, and by whom to cancel the said mortgage, and thereafter give indefeasible titles to portions of the property sold, at same time protecting the interests of both wife and husband. There would have been no difficulty in obtaining a large sum on mortgage, but that was inadvisable, as the property was becoming very valuable, was wanted, and must be minutely subdivided on sale. The plan adopted was for a friend to buy the whole property at sheriffs sale, consequent on all amicable suit by Devagne’s executor, reimburse outlay by sales of lots in his own name, and then reconvey the remainder, unencumbered. Benjamin R. Morgan, one of the most esteemed citizens of Philadelphia (admitted to practice as attorney in 1785, secretary of the Philadelphia Library from 1792 to 1825, and judge of the District Court in 1821), was the disinterested friend who performed this service; and to him all the property was conveyed by sheriffs deed dated April 3, 1809. 38 In said deed, among the various tracts described, neither the Governor’s Mill, nor the “mill land,” nor mill-pond is mentioned. Although anticipatory, it is proper here to mention that Mr. Morgan, after conveyance of the Governor's Mill and other land therewith, about to be mentioned, and the sale of certain other lots of ground, conveyed in 1812, “out of friendship to Turner Camac”—as expressed in the deed—all the residue of the tracts and lots comprising Sarah Masters Camac's estate to two trustees “for the benefit of Turner Camac and Wife.” This formed what for many years was known as the Camac Estate.

1 P. and L. Corr., Vol. 1: 60.

2 Annals of Philadelphia, ed. 1857, Vol. 1: 40.

3 P. and L. Corr., Vol. 1: 96.

4 $730. See note, P. and L. Corr., 1. 210, where Penn reckons the Pennsylvania pound to be 12/16 of the £ Sterling of $4.8615 (present), value, say $3.65.

5 P. and L. Corr., Vol. 1: 127.

6 The inferior work appears to have been on the Schnylkill Mill. No one has identified the location of this establishment; and the P. and L. letters do not again mention it. Scharf and Westcott’s ‘History of Philadelphia’ says (1: 153) without explanation, “Penn had two mills on the Schuylkill,” Also (Id., 1:46) that William Bradford, writing to the Governor, about the year 1698, states he and Samuel Carpenter were building a paper mill “about a mile from Penn's mills at Schuylkill.” That there was a mill known as “The Schuylkill Mill,” is proved by an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette, of July 21, 1737, which commences: “Absented himself from the Service of Richard Pearne, at Schuylkil Mill, in Blockley Township, Philadelphia County, an indentured Man,” etc. Mill Creek, still known by that name, was once a considerable stream, and the two principal mill-seats on it were the one near its mouth, just below “The Woodlands,” where was very early a corn-mill, known as Joseph Growden's in 1711. More recently it was for many years the Maylandville woollen-factory, and for some years after 1816, had been a saw-mill with snuff-mill annexed.

The other principal site was a short distance north from the present north-west corner of Forty-Sixth Street and Haverford Avenue, where was formerly a cotton mill occupied 1830-1843 by William Almond, whose store was at 39 North Front Street. This mill went into possession of Richard Blundin about 1843, and was by him much enlarged, and made into a cotton-woollen mill. About 1858 Captain John P. Levy bought this property from the Blundin estate; and the buildings still stand, forming part or the Levy estate. The site last named is, I think, the only one in the Schuylkill district likely to have been the “Penn Mill” or the “Schuylkill Mill.” It is located one and one-eighth of a mile from the Schuylkill River, and one and three-eighths of a mile in a direct line from the Maylandville site. It appears also to have been the water power which, at and before Penn's arrival, was known as “Captain Hans Moen’s Great Mill Fall,” and respecting it there is the following minute from the proceedings of The Upland Court in 1678: “The Cort are of opinion that Either Captn hans moens ought to build a mill there (as hee sayes he will) or Else suffer an other to build for the Comon good of ye parts.” [Up. Ct. Ree. (reprint), pp. 114, 115, His. Soc. Penna. See also; Wharton's Surveys, September 20th, 1675, in Sur. Gen. Off. Harrisburg.]

It is not improbable that Hans Moens declined to build, and that Penn exchanged other land for the 120 acres and the mill-site which Moens held by patent confirmed to him March 10, 1669-70, 0.S., by Governor F. Lovelace, of New York. [N.Y. Patents, Exn. Book 8, page 436.] This was done by Penn in the case of the Cocks and other Swedish holders of good titles to important portions of the site of Philadelphia. Moens appears to have been allied to the Cock family, for there is frequent mention in the old annals of Moens Cock.

7 P. and L. Corr., Vol. 1: 182.

8 $1460 Pennsylvania money of present value. Vide P. and L. Corr., 1:209, and note 210. The value of the Pennsylvania pound was afterwards fixed at a (present) value of $2.66-2/3.

9 P. and L. Corr., 1: 142.

10 P. and L. Corr., 1: 182.

11 Exemplification Book, No. 6, page 84, Rec. of Deeds, Off., Philadelphia

12 “The land granted from the mill at town’s end” was probably part of the tract long known as “the Governor's pasture,” which extended south from the mill nearly to Laurel Street, and joined the property of Daniel Pegg.

13 P. and L. Corr., Vol 2: 254.

14 James Logan's idea of grist-mill property must have changed after this, for on April 4, 1718, he bought, paying £100, one-quarter interest in the “Potts Corn Mill,” of Bristol Township. [D.B. “E.7, No 10,” page 477.] The mill and its fifteen acres of land were then worked for account of James Logan, Richard Hill, Joseph Redman, and Isaac Norris.

15 Annals, Vol 2: 388.

16 Keith, in “Provincial Councillors of Pennsylvania,” page 453, states that Thomas Masters’ wife was Sarah Righton, who was the mother of William Masters, to be hereinafter mentioned. In the will of Thomas Masters, Senior, although no wife is mentioned, he stipulates for a home during her life for “my mother [mother-in-law], Sarah Righton.” There is no reference to the patent, nor to “Tuscarora Rice,” in said will.

17 See Vol. 4, Brit. Pats., also Brit. Pats., Agr. Div. p. 2, and framed copy of drawing in Franklin Institute, Philadelphia. Minutes of the Provincial Council show that on July 15, 1717, Thomas Masters applied for permission, which was granted, to record this patent and another, also the invention of his said wife, Sibilla [English patent No. 403. granted Feb. 18, 1716], “for the Sole Working and weaving in a New Method, Palmetto, Chips, and Straw, for covering hats and bonnets, and other improvements in that ware” (Brit. Pats. Wearing App., Div. 1, p. 1).

18 Sergeant's Land Law, 39. Lewis, Orig. Tit., 42.

19 Judge Huston (Land Titles, 231) says, that William Allen, barrister, of London, and afterwards Chief Justice, of Pennsylvania, furnished the funds to pay off the balance of this mortgage.

20 Recorded in deed book E, No. 7, Vol. 8, page 360. Both this and the 80-acre tract are shown on Reed & Halls map of 1750, as lying between the west branch of the Cohocksink and the creek itself. The 200 acres surround on the west and northwest a tract of 12 acres marked T. Masters, in the forks of the two streams, which last-named portion must have included the mill-pond, not shown, however, nor is the race. It is interesting—as recited in the old deed—that Dr. N. More, of London, was buried on the 80-acre tract, which appears to have been his residence for some years. He was —for that period—a very wealthy man, president of The Society of Free Traders (see its constitution, etc., in PMHB, Vol. 1: 37) and possessor in his own right of 10,000 to 15,000 acres of land in and near Philadelphia—a portion of which tracts formed the “Manor of Moreland.”

21 Deed book E, Vol. 5: 134.

22 "Att a councill Held att philadelpbia Die Martis 23 Aprill 1695, 5 in the afternoone,"— in regard to certain debts due by Nicholas More's estate, and to raise funds for educating his minor children, it was ordered: "That the said John Holme might be permitted & allowed to sell the plantaon of Green-spring, with all ye Lands & improvements thereto belonging… and that the members of Councill for the Countie of philadelphia, or anie two of ye, may supervise the said sales."... Colonial Records, Vol. 1: 476.

23 One of the fow modes of speculation among business men in those early days, is indicated by an advertisement which appeared in the Philadelphia papers in 1739, over the signature of William Masters and two others, offering to sell the time of a large number of Palatines [Redemptioners], who had just arrived in a ship from London.

24 Prov. Coun. of Penna., page 453, etc. The dwelling of the plantation, as shown on a map made for the British General Howe in 1777, was near what is now the northwest corner of Eighth and Dauphin Streets.

25 Proved January 30, 1761, Will book M, page 38. Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Fox, and Joseph Galloway were made executors, and with Mrs. Masters were to be guardians of the three minor daughters.

26 This house, or the upper stories fronting on Front Street, was, as shown by an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette, of May 26, 1790, the clock and watch store of Ephraim Clarke, and his residence, and probably had been for some years thus occupied. There was a clock face in the transom over the front door; and it was an almost daily practice with Washington to walk to the London Coffee House corner, opposite, to compare his watch with this standard regulator. Benjamin and Ellis Clarke, sons of Ephraim, continued the business; and a son of Ellis, I believe, remained there as watchmaker. The old clock was in the transom until the year 1843-4, when the present granite and brick store was erected on the site, after immense trouble from water which invaded the foundation.

27 See one on January 3d. Wagstaff & Hunt also advertise concurrently in same journal, mustard for sale “at the sign of the Key in Market Street, or at their Mustard Mill, in Tradesman Street, near the New Market, Society Hill, Philadelphia.”

28 PMHB, 4: 492.

29 The deed of the Mill Land to Thomas Masters recites: “Together with all that grist or corn mill and mill thereon… and all the mill houses utensils and materials whatsoever to the said mill or mills appertaining;” also, “To have and to hold the mills erected.”

30 Keith, Prov. Conn., 427, 428, has the following curious statement: “After war broke out be [Richard Penn] wrote to a friend, that be was thankful his marriage had provided him with sufficient fortune to live in England, away from the scene of trouble."… In England he became very poor. His attorney wrote in 1780: “My friend R. Penn’s distresses have almost drove him to distraction. I understand from Mrs. Penn, they are now kept from starving by the bounty of Mr. Barclay.” Richard Penn visited Philadelphia in 1806, and lived for awhile at 210 Chestnut Street between 8th and 9th Streets. He died in England, May 27, 1811, aged 76.

31 Hill v. West, 4 Yeates, 142, 144.

32 Hurst v. Durnell, 1 W. C. C. R. 262.

33 Sergeant’s Land Law, 44; 1 Smith’s Laws, 48.

34 Recorded in Partition deed book, Docket No. 1, Supreme Court, page 310. By this partition there was no prejudice to the life right of the Widow Masters in certain parts of the property, as above mentioned. She died in London, in 1799.

35 It is evident that tract No. 12, or four acres and eighty perches, could not yield all this large property, including the race and mill-pond, since the latter alone contained two acres and forty nine perches. This may seem of inferior importance, but in bries of title exactness is needful.

36 Scharf & Westcott's ‘History of Philadelphia,’ Vol. 3: 2310 (1884). Bishop, ‘History of American Mfrs.’, Vol. 2: 51, also says: “A number of carding machines for cotton and wool. were recently (1794) constructed, and eight spinning frames on the Arkwrigbt principle, and several mules were erected at the Globe Mill in the Northern Liberties.” Introduction to Vol. 4: 106, U. S. Census 1860, has the following on this effort: “The labor was done chiefly by boys, each of whom was able to spin in ten hours 97,333 yards of flaxen or hempen thread, using 20 to 40 pounds of hemp according to fineness, and another could weave on the machinery 15 to 20 yards of sail-cloth per diem.”

37 It is quite possible that for some years his son John Hewson, Jr., continued a print works at or near the former place; for, as late as 1808, he is mentioned in the directory as a calico printer, located or residing in Beach Street above Maiden [Laurel] Street.

38 Book C, Sup: Ct. Rec., Philadelphia, page 378.

-----

The Governor's Mill and the Globe Mills, Philadelphia. Part 2

The Globe cotton mill enterprise, though of modest commencement, yielded surprising results. Truly momentous to the United States was the decade 1800-1810, for then were being made most strenuous efforts to introduce cotton manufacture by machinery, newly invented, rude in construction, and jealously guarded by British government. 1 Cotton carding and spinning machinery, however, such as it was, had been made in 1791 by John Butler, 111 North Third Street, Philadelphia; and in 1803, “Billies” of 12 spindles at $48, for family use, and larger “Jennies” and "Mules" were made by Joseph Bamford at 5 Filbert Street, and also by Mr. Eltonhead. The latter sold “carding engines” at $40, drawing and roving frames $200, and mules of 144 spindles at $300. 2 Robert Lloyd patented February, 8, 1810, an improved loom for weaving girth cloth; and the important invention of machine-cards by Elizur Wright, Walpole, Mass., also dates from 1810.

In 1804 cotton manufacturing became successful in Connecticut; and in 1805 Messrs. Almy, Brown & Slater, of Rhode Island, whose mill, and the attempts of Almy & Brown dated from 1790, had 900 spindles at work. Woolen carding, and spinning by machinery, for fine goods, was also being attempted at this period by Wadsworth, at Hartford, Connecticut. Although some excellent cotton goods had been manufactured before 1800 in Philadelphia and a few other places, it was Samuel Slater who first made the business permanent and profitable. American efforts at cotton and woolen spinning by machinery were wonderfully stimulated by the non-intercourse with England, just previous to and during the war of 1812-15; 3 this was the main reason of success which attended the Globe Mills.

It thus plainly appears that the small commencement about to be recorded was in the van of cotton manufacture in the United States, and well deserves historic notice, had there been no other interesting connection. By deed dated April 4, 1809, 4 witnessed by Turner Camac, Benjamin R. Morgan conveyed to Adam Seybert, Seth Craige, Charles Marquedant, and Thomas Huston, in equal parts: “All that certain mill called or known by the name of the Governor's or Globe Mill, and the lot or piece of ground on which the same is erected.” This conveyance comprised the mill-pond and dam (2 acres and 49 perches), a strip of land 44 feet in width along and including the mill-race, and extending to the mill lot, besides “Bathtown,” and northward to the intersection of Third Street and Germantown Road. On the east, the street last named was the boundary, and Third Street the principal limit on the west; “Being,” as recited in the deed, “the same Lot of Ground allotted (inter alia) to Sarah Masters,” etc. The deed further says, page 333 of record: “Together, also, with the free and exclusive use and privilege of the mill-race from time to time, and at all times, until the above-described lot of ground and every part thereof shall absolutely be abandoned as a scite for any mill and Water Works, and of the waters thereof leading from the Mill Pond on the second above-described lot [marked No. 2] or piece of ground to the aforesaid mill, and of the following described strip or piece of ground through which the said race passes” [44 feet in width, as above mentioned]. On page 334 of record, the mill-dam is mentioned, privilege given to take water from adjacent lots “formerly of William Masters,” and right to keep the mill-dam logs "at the present [1809] height.”

The course of the race was slightly S. W., not far north from the creek; and the former, crossing Third Street a short distance above the present Girard Avenue, not then located, turned directly south when about half-way between Germantown Road and Third Street, immediately in the rear of a lot where John Holmes afterwards erected a double brick house fronting Germantown Road. Traversing the space, later Franklin Street, and still later, as widened, Girard Avenue, the race delivered water to an overshot wheel, “under the floor” at east end of the old mill. The water then flowing 100 feet further south, entered the Cohocksink Creek, which passed through the vacant lots of Bathtown, where, for many years, was a refreshment house and public garden. The position of the water-wheel is worthy of notice, it being usual in almost all the older water-mills of the 18th century to place the wheel outside. It also shows more plainly, that originally the slope southwest from the present level of Germantown Road to the creek must have had an elevation of 15 or more feet.

The intention of the parties was to use the wheel and its appurtenances, and erect a new brick factory on the firm old foundations, which was eventually done, making the height 3-1/2 stories on the north, and 4-1/2 stories on the south side. This was the smaller of the two rear buildings, as they will be hereinafter designated. The unusual thickness of the ancient walls and large size of the stones therein made their demolition difficult. This is attested by one still living, who, as a youth, aided in the work. 5

Doubtless many unforeseen difficulties and much delay arose, for, on June 26, 1809, Adam Seybert sold, without profit, all his right in the property to Seth Craige, 6 and retired from what might reasonably have been considered a most doubtful enterprise. Dr. J. Redman Coxe—whose brother, Tench Coxe, the distinguished statistician, along with Alexander Hamilton early and ably advocated American manufactures—is said to have been interested in this venture. White's Memoir of Slater, page 187, remarks: “As early as 1808, $80,000 were invested in the Globe Factory, Philadelphia, in which Dr. J. Redman Coxe was concerned.” It appears, therefore, that in more ample capital, the first firm, Craige, Marquedant, and Huston, had great advantage over some parties who early attempted cotton manufacturing in the United States without success. Dr. Coxe could not have been interested in the real estate, as his name does not appear in any recorded transactions, nor in the various agreements, etc., afterwards made, as far as I can discover.

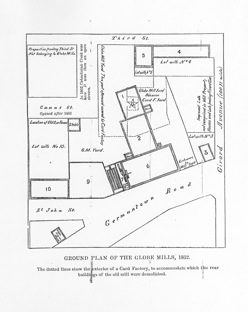

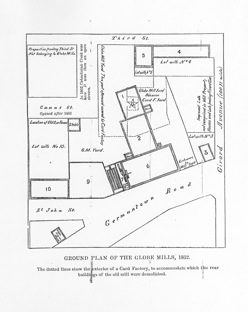

The brief of title of the Globe Mill property—commencing with 1723—says in one place: “And the said Seth Craige, Charles Marquedant, and Thomas Huston 7 have erected a factory on the undivided part of the said last-described lot of Ground.” This was the small mill building already described, size 40 x 56 feet, three stories with attic; and, by reference to plan hereto annexed, its centre is shown as coinciding with that of an outside stairway to the latest extension of A.M. Collins, Son & Co.’s card-board factory, further mention of which is to be made.

Mr. Westcott (Vol. 3: 2317) thought Alfred Jenks, who had worked with Samuel Slater, and came to Philadelphia in 1810 with drawings of cotton machinery, built the first machinery for the Globe Mill. This, however, was not the fact; it was made by several independent but good mechanics, one a carpenter for the wooden frames, under direction of a person (name forgotten) located near the central part of the city. The sheet cards were imported. Mr. Jenks afterwards made a large quantity of improved cotton machinery for the 2d, 4th, and 5th extensions of these mills.

The second rear building, much larger than the first, being 50 x 67 feet, five stories in height, besides basement, and with two attic stories in the lofty hipped, shingle roof, was erected in 1813, during the “prosperous time” of the war. At its west end was placed an upright steam engine, having cylinder, boilers of 45 horse-power, all constructed by Daniel Large, 8 a noted Philadelphia machinist, located at 513 (old number) North Front Street, and foundery Otter Street below Germantown Road.

The 2-1/2 story brick house, still at S. E. corner of Girard Avenue and Germantown Road, occupied since 1856 as a store, was also erected in 1813. For some years it was office, ware-room and sales-room; afterwards for 38 years a dwelling, and long occupied by the superintendent. By legal partition, January 19, 1813, the several interests of the mill proprietors were rearranged; and by deed dated December 22, 1813, Charles Marquedant and wife conveyed one-quarter interest in the premises and business to John Holmes. 9 The mill property thus became owned one-half by Seth Craige (the grandfather of the final owners), one-quarter by John Holmes, and one-quarter by Thomas Huston.

During the war of 1812-15 the firms named started a calico-printing department in a frame dye-house hereinafter mentioned, using wooden blocks; Francis Labby, a Frenchman, was manager. 10 Printing cloths were in part purchased, and in part woven on hand-looms in several small 2-1/2 story buildings on the mill lot, 150 feet, or more, north from the mill-spooling and warping being done in their lower stories. Large quantities of heavy woolen felted goods were purchased and printed in imitation of leopard-skin, for army use. This printing business was very profitable for several years, but excessive importations almost ruined it soon after peace was declared. 11

The narrow three-story building, still at S. E. corner of Girard Avenue and Third Street, now a children’s coach factory, was erected in 1816 to accommodate weaving of saddle girthing, tapes and fringes oil hand-looms. This also, had been a most profitable department during the war; and the girthing and tape did not suffer as much as some other textile business on the advent of peace. Some of the tape looms then wove 6 to 10 pieces at once. T. Wilson, in “Picture of Philadelphia in 1824,” says, of the Globe Mill: “It employs about 300 hands, and manufactures ginghams, drillings, checks, shirtings, and sheetings, has 3200 spindles, and uses 5400 lbs. cotton weekly.” All the check goods then made were woven oil band-looms—power looms with revolving or rising boxes, to change shuttles, not having been introduced into the United States cotton mills until about 1830.

In 1828 Craige, Holmes & Co. made their fourth extension by erecting substantial 2-1/2 story brick building, with basement, fronting 30 feet on Third Street, 40 feet in depth; it communicated directly with the narrow building previously mentioned. In the basement were placed boilers and an upright steam engine of 48 horse power, the engine being made by John Walshaw in the machine shop located in basement of rear buildings. This new portion was connected by a shaft with the first rear building, to supply power when water failed, which began occasionally to occur. 12 The first story of this extension was used for office, sales and store-rooms, the second story for girth looms renioved from the narrow building, while in the latter was placed additional cotton machinery.

There had been built, date now unknown, but probably 1812, a frame dye-house near where the race entered the creek, and not far from a small brick stable, shown on the accompanying plan. Here, besides that worked in the mill, dyed cotton yarn was woven by outside hand-loom weavers; and the business last named became in time a very important department. A portion of this dye-house was of slats, there being connected with it a warp sizing room. Water was conducted from the elevated race and distributed by open wooden troughs; later, small leather hose was partly adopted. Edward Healey, an Englishman, for more than 30 years chief dyer of the Globe Mills, lived 25 years in the ancient 1-1/2 story stone building mentioned as once fronting on Germantown Road. For several years after the commencement, all the assistants on yarn dyeing, about six in number, were women.

The cotton carders at this factory were: (1) William McRobb, of Scotlaiid, who was entirely deaf and dumb; (2) James Low, England, and (3) John Stafford, England.

During the war of 1812-15, a considerable quantity of No. 100 cotton yarn was spun on one mule. It was used for “tambour embroidery,” and sold for $5.00 per pound.

In the Philadelphia Gazette of April 22, 1829, Craige, Holmes & Co. advertise that they have completed the enlargement of their factory, and offer “Globe Mill cotton yarn” at their store, No. 110 Market Street. Under date, March 30, 1832, 13 Craige, Holmes, & Craige, replying to special industrial queries, sent in the interest of home production, by Mathew Carey and C.C. Biddle, stated, inter alia, that they employed a capital of $200,000; 14 had three buildings erected in 1810, 1813, and 1816, with two steam-engines and a water-wheel; 47 looms for saddle girth, and 9126 spindles for cotton yarn of numbers 14 to 20. They used 518,000 lbs. cotton in 1831, also 52 bbls. flour, and 3120 lbs. tallow in sizing warps. They employed 114 men and women, the former averaging $8.50, and the latter $2.62-1/2 per week; also 200 boys and girls, whose wages averaged $1.37-1/2 per week. The firm remarks: “Apprentices [the number was generally twelve] have one quarter’s schooling annually.” 15 It is singular that this reply did not mention the fourth extension; 1828, herein given as date of the latter, is correct. After 1832, besides yarn and various other goods, the firm made a large quantity of cotton fringe on hand-looms, one person to each loom. It is asserted that this was the first place in the United States where fringe was formed upon looms.

Mr. Townsend Ward, in a short account of the Governor’s Mill, says: 16 “The dam appears to have been standing as late as 1830.” The above record shows it was used in 1832; and, I am informed, the water flowed from the race into the dye-house for several years after the wheel was disused. It is probable that the mill-dam and race only ceased as a water power in 1839, consequent on the opening of Franklin Street through the mill lot. A wide street must have been anticipated here in 1813, judging, by the location of the 2-1/2-story office (No. 3) then built. Upon December 19, 1838, certain property owners petitioned the Court of Quarter Sessions that Franklin Street might be opened from Second to Fourth Street, "through land of Thomas Craige and others." A jury being appointed by the Court rendered a report February 13, 1839, awarding damages for land taken from the Globe Mill premises and from other parties (probably also for loss of water-power, though it is not mentioned) the amount for the mill land, etc., being $12,050. 17 In 1855, Franklin Street was widened from 32 to 100 feet for part of its length and called Franklin Avenue, then Girard Avenue; and in 1858 the last-mentioned name was extended to the whole street.

In 1840, the very substantial 5-story factory, 54 x 100 feet, fronting on Germantown Road, with attic and basement, was erected—the second rear building being directly connected by openings, for which purpose the east wall was taken down. There were also at same time built an engine-room and 2-story boiler and drying house, with a massive but not lofty stack; also an extensive 1-1/2 story dye-house, and a 4-story building, 34 x 69 feet, with basement, the latter structures fronting St. John Street. These additions were all made by Messrs. William Einwechter & Sons, for many years noted builders in Kensington.

A powerful horizontal steam-engine, of unusual stroke cylinder about 15 x 60 inches, and cutting off steam at 2/3, was purchased from Smythe's great distillery, 18 once located near the Schuylkill below Callowhill Street. Engine and boilers were rearranged and placed by James T. Sutton & Co., then at Howard and Franklin Streets. There was connection by a square 2-1/2-inch iron shaft, from engine to large mitre wheels in the ceiitre of main basement, and thence to rear buildings. Power was transmitted to second floor of main mill by massive spur cogwheels of eight and three feet diameter with 5-inch faces, one of the large wheels being on the main shaft of engine projected through the end wall; and when working this gearing made a loud, unpleasant clanging. A wooden drum on the north wall of rear buildings furnished, by belting, most of the power to that portion of the mills. This engine proved sufficient for the whole establishment, and was very economical. It was replaced in 1876 by one of cylinder 18 x 36, made at the People’s Works. The new dye-house received water from city pipes, but distributed it in open wooden troughs, an arrangement which remained in use until 1852. City illuminating gas was introduced into all parts of the establishment as soon as this fifth improvement was finished.

The first story of the St. John Street factory was used for awhile as office and sales-room, and for storage of yarn and goods; into the upper stories were removed the girth looms from the Third Street mill and some band-looms for piece goods. In the 4th and 5th stories of the main mill were placed in 1843-4 a large number of power looms, mostly plain, driven from long wooden drums of 12 inches diameter fixed on rough iron shafts. These looms were made partly by Thomas Wood, Philadelphia, and partly by Alfred Jenks, Bridesburg.

As already intimated, the basement, or lower story on the south front of the rear buildings, had for many years been occupied as a machine shop and place for repairs—having a number of lathes, and sundry machine tools. A square 2-1/2 inch iron shaft ran through the centre, and upon it were pulleys made entirely of wood; and such use of this portion of the works continued until 1851. 19

In 1849, the St. John Street factory was rented to James Lucas, who afterwards bought it and herein for nearly 12 years did considerable business, obtaining cotton yarn from the Globe Mills and elsewhere, and distributing it principally for dyeing and for weaving on outside hand-looms. He also rented for a few years some of the power looms in the main building, but ceased business in 1861, when several reasons rendered his modes impracticable. He was of rather eccentric character, and one peculiarity was covering his bills, notes of hand and labels of goods with aphorisms. Previous to 1849, and from about 1838, he had been a “trader” of cotton goods by means of wagons through Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware; and by this primitive mode he was distributed a considerable portion of the Globe Mill hand loom piece-goods. He died about 1872.

During the 42 years of cotton manufacturing at the Globe Mills, deeds, transfers, agreements about annuities and dowers, releases of dowers, etc., were very numerous. Several owners died intestate, increasing the legal papers; and there was a second legal partition in 1832. On the dissolution of the last firm of Craige, Holmes & Co. in 1851, Seth Craige and Thomas H. Craige. sons of Seth W. Craige, together owned one-half, the estate of John Holmes one-quarter, and minor children of a deceased Craig one-quarter. Thomas Huston’s interest, he being deceased, had previously been purchased by some of the above-named owners. During 1851 various deeds and agreements, and a public sale in partition, January, 1852, rearranged the whole property, Seth Craige becoming (including his former right) possessed of over three-fourths thereof. Early in 1852, Thomas H. Craige and Mrs. Holmes transferred to Seth Craige their interest in a strip 32 feet wide on the plan for partition, and intended for a street, running from Canal Street to Girard Avenue, etc.; and Seth Craige became sole owner of the premises.

In April, 1852, Mr. Craige sold the narrow building on Third Street to W. W. Fouché, dentist; and in May of said year (all cotton machinery being removed) the buildings and premises, excepting the St. John Street factory, were leased to Samuel H. Needles, woolen manufacturer, then located at the Star Mill, Howard and Jefferson Streets, who soon started 13 sets woolen machinery, including 120 four-box power looms and finishing arrangements for fancy cassimere, thus changing the establishment to a woolen mill, which general character it has since retained. 20 In the winter of 1855 this occupant removed; and rooms in the various buildings were gradually rented with power to textile manufacturers, at times exceeding ten in number.

Two generations have now passed away since the demolition of the Governor’s Mill and tentative commencement of cotton manufacturing on the exact site. A third operation is fast progressing, nearly half of the factory has disappeared, and the remainder—a woolen mill—may at any moment be destroyed by fire. It is certainly, therefore, proper that two such establishments, each a large contributor to the early industrial development of Philadelphia, should receive due historic notice.

1 See 21 Geo. III. c. 37, in 1782, also another restrictive Act, 1783.

In 1786, a brass model of Arkwright’s spinning machinery, made for Tench Coxe, Philadelphia, was confiscated in England on the eve of shipment. In 1787, two carding and spinning machines, imported at Philadelphia, were bought by English agents and reshipped to Liverpool. At the small cotton factory, Beverly, Mass., there were, in 1789, one cotton card and a “spinning jenny,” which had cost fully £1100 sterling. Bishop, History of American Manufactures, Vol. 1: 399, 418.

In 1791, Whitney invented the cotton-gin—without which cotton machinery was of little value—but it was stolen, his rights disregarded, and he and his heirs never compensated by Congress for the national benefit from his invention.

2 Bishop, HOAM, Vol 2: 167,188.

3 “In 1803, there were only four cotton factories in the United States, but when the period of restriction began, in 1808, the importation or foreign goods was first impeded, and soon entirely prevented. In 1804-8, much more activity prevailed, for in the latter year 15 mills had been built, running 800 spindles. In 1809, the number of mills rose to 62, with 31,000 spindles [only 500 average, however], while 25 more mills were in course of erection.” Taussig, Protection to Young Industries, p. 25.

4 Deed Book I. C., No. 1, p. 331.

5 Since publication. of part first of this paper, I have had reason to consider the Governor's Mill as of 2-1/2 instead of 1-1/2 stories. This is confirmed by the only person I know who saw the old structure, and it explains the wheel being "under the floor," i.e., under the floor of the main story. There was a low basement with windows and a door loolking southward, while the north wall was blank against the steep hill. The principal story was more lofty than the basement; and into the former was the chief entrance, in the north side, from the sloping bank. Not far from the south front was a fine spring of water, carefully walled around with large stones.

6 In Mr. Thompson Westcott's brief notice of this effort (Scharf & Westcott, H. of P., Vol. 1: 522) there are several inaccuracies. The date is 1805, Seth Craige the only proprietor, contracts stated as made with a saddlery firm at 110 Market Street (actually the city office of the Globe Mill), and Mr. Houston and John Holmes taken as partners in 1816. It further erroneously says that woolen goods were made by Craige, Holmes & Co.

7 Huston, viewing the former constant misspelling of names, resembles too much that of John Hewson (yet to be mentioned as located at the Globe Mill in 1803), to permit much doubt that Thomas Huston was related to, if not the son of the said John Hewson. Conjecture is reasonable that Thomas Huston had by some mode obtained knowledge of cotton manufacturing, without which probably the venture would not have been made. Seth Craige was largely in the saddlery and saddlery-hardware business, Huston was one of his journeymen, and Seybert and Marquedant are described in the deed of April 4, 1809, the former as doctor of medicine, and the latter as merchant.

8 Daniel Large was the youngest apprentice of the first steam-engine firm, Boulton & Watt, of Birmingham, England. Some of the frame buildings, formerly portions of his shop, are still standing in the rear of Front Street above Laurel.

9 As previously stated, the firm had been Craige, Marquedant & Huston. From 1814 to 1828, there was the plated saddlery firm of Craige, Huston & Co.—store 110 Market above Third Street—concurrent with the cotton manufacturing firm of Craige, Holmes & Co. at the Globe Mill, and sales-rooms also at 110, and awhile at 287 (old numbers) Market Street. In 1832, the firm last named became Craige, Holmes & Craige, but after a few years was changed back to Craige, Holmes & Co.; the city office in 1847, and until liquidation, was at 12 North Fourth above Market Street.

10 Scharf & Wescott, His. of P. Vol. 3: 2317, record that Francis C. Labbe started calico printing at 206 Cherry Street in 1812, and after four years discontinued it to become a dancing master. It is quite probable, however, that soon after commencement, from want of capital, he and his works were transferred to the Globe Mill. I think my aged informant, who is the only relic of the print works employés, could not, independently, have come so near the name first above given unless the fact was as already stated. Although printing cottons by machine from copper cylinders was adopted, with imported machinery, by Thorp, Siddall & Co., at their works near Germantown, Philadelphia County, in 1809, it was ten or more years before much progress was made in the United States in introducing this great improvement.

11 The advantages of home production and the circumstances of war to certain kinds of business, are exhibited in Grotjan’s Philadelphia Sales Reports, published during 1812, ‘13, and ‘14 at 58 Walnut Street. In September, 1813, ordinary sizing flour (sour) was $7.00, ,and good flour $8.00 per barrel, and Upland cotton 14-1/2 cts. 60 days. At same date the commonest calico sold for 23 to 24 cts., fancy at 50 to 60 cts., and super calicoes at 57 to 68 cts. per yard, all at 60 days. On December 5, 1814, while flour had advanced but little, and Upland cotton to 23 to 27 cts. per pound, commonest calicoes sold at 56 cts., good and super calicoes 76 to 83 cts., and 64 muslin at $1.171 per yard, while narrow cotton tape was $5.50 per gross, all at 60 days.

12 Some years previous an overshot waterwheel, of same size as the original wheel, but with independent shaft, had been placed five feet distant from the old Wheel, and so arranged as to be collected therewith when water was abundant. The crowding in of much machinery had begun to seriously tax the water-power, and the latter was also diminishing.

13 Statistics of Manufactures of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Collected 1831, 1832: 215.

14 The proprietors of the Globe Mills had always ample capital, not only to make but to distribute their goods. The dry goods commission business, prominent for the past 50 years, had an early example, if it was not the actual commencement, in "The Domestic Society," incorporated at Philadelphia, March 11, 1805, to encourage the starting of manufactures by making loans on security, and advancing money upon dry goods to half selling prices, charging 6 per cent. interest, and 5 per cent. on sales. Transactions of the society were not large, but for some years it paid 6 to 8 per cent. dividends. Office was at 6 South Third Street. (See advertisements in Philadelphia Gazette, January 13, and March 11, 1809.)

15 It is of interest, as showing the great improvement, of late years, in the condition of factory employés, that until nearly 1840, the hours of work in these and other textile mills were from sunrise to sunset in summer, and from 7 A.M. to 8 P.M. in winter, with half an hour for dinner. This averaged 13 hours daily; and the present half holiday was unknown. The proprietors of the Globe Mills were not more blamable than others for such long hours; it was the custom, and there is evidence, beyond that above given, of much kindness and consideration towards their apprentices and other mill hands. The working hours of the Lowell cotton mills about this period were even longer—13 to 14 hours—according to a paper recently published by Mr. Edward Atkinson, of Boston, entitled “What Makes the Rate of Wages.”

16 PMHB, Vol. 5: 3, 4.

17 Road Docket Rec. of C. of Q. S., Vol. 12: 433, 435.

18 This establishment will be recollected by many as having been sui generis, without successor in Philadelphia.

19 About 1830 leather belting began to be more common in factories for the main and other principal portions of power. There were at that time no regular belting factories, and the belts were of rather rude construction. The connections from main driving power in cotton mills were then, and remained for some years, chiefly heavy upright iron shafts and all-iron cog-wheels, after the prevailing English mode. John Craige furnished belting for the Globe Mills for nearly 40 years. His saddler shop was in a small 2-story house, still standing at 1306 Germantown Avenue above Thompson Street.

20 Said Needles made various alterations, viz., two stories added to dry-house, new area and area windows, and high paling to main front, outside stairway to rear buildings, w. cs. to five stories, underground shaft to Third Street mill, cast-iron spur wheels removed, and water pipes and steam fixtures placed in dye-house.

© Samuel H. Needles, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1884), Vol. 8 , Part 1 pp. 279-299; Part 2 pp. 377-390.

Part 1

No historical sketch has been written of the water-power grain mill built for William Penn in the Northern Liberties, on Cohocksink Creek, where, for one hundred and nine years, it occupied a site afterwards used for the first “Globe” cotton mill. There is also not any connected record of the Globe Mills—the most conspicuous establishment in Kensington for many years, and until about 1850 the largest textile factory in Pennsylvania with possibly one exception. As representative places, the Governor's Mill was a diminutive prototype of monstrous flouring establishments at Minneapolis and in other cities; and the Globe Mill was one of the few factories which, in 1809, despite numerous difficulties, were striving to introduce into the United States the use of cotton machinery. Those members of the Craige, and other families, who were long identified with the latter establishment, having been some years deceased, it seems appropriate that a record of its rise and progress should now be made, before circumstances therewith connected are forgotten or lost.

No mention is made of these two mills in Hazard’s or Day’s Pennsylvania historical collections, and only brief and indirect notices of them in the admirable annals of Messrs. Watson, Westcott, and Ward. Although the first corn and cotton mills of other States are well noticed in Bishop’s ‘History of American Manufactures,’ there is no mention therein of the Governor’s Mill, and very slight reference to the Globe Mills. As the “Roberts Mill” at Germantown dates from about 1683, one was built at Chester for Penn and others in 1699, and Thomas Parsons had one at Frankford in 1695, it is probable the Governor's Mill (built 1700-1701) was the fourth water-power grain mill erected after Penn's arrival. All the machinery for it, of very rude description, was imported from England, as was also done for its predecessors; and there is reason to believe that English bricks were used for certain parts of the building. Power was derived from Cohocksink Creek, formerly called Coxon, Cookson, and even Mill Creek—the race descending from a pond covering almost three acres at the junction of the western branch, which entered said pond near the present northeast corner of Sixth and Thompson Streets.

The triangular sheet of water was bounded on the south by a lane, now Thompson Street, east by “Old York Road,” now Fifth Street; and the third irregular line stretched from the corner above named to where the creek entered, about the present junction of Fifth Street and Timber Lane, now Master Street. The main stream, rising near the locality now known as Twenty-Fifth and Clearfield Streets, turned from its east course just below the intersection of Fifth Street with Germantown Road, and ran south into the said mill-pond. On Foley’s map of 1794, the ground between the creek and race is depicted as swampy, and it is known to have been frequently inundated. “Green Mill” is the name given to this mill on said map, which will be hereinafter explained. Dimensions of the one-and-a-half story building were forty by fifty-six feet, walls very thick and of extra large stones, windows few and small; and the double-pitched shingle roof had heavy projecting eaves.

The earliest facts respecting the Governor’s Mill are found in the “Penn and Logan Correspondence,” where, however, they are neither frequent nor satisfactory; and no mention is made therein of mill property transfer by William Penn or his agents. When returning to England, after his second visit, Penn, writing from the ship Dolmahoy, in the Delaware, November 3, 1701, 1 says: “Get my two mills finished [one was the Schuylkill Mill, yet to be noticed] and make the most of these for my profit, but let not John Marsh put me to any great expense.” The Governor’s Mill, though it was certainly a great accommodation to many of the inhabitants of the new town and the Liberties, did not prove a profitable investment to the owner. Part of the difficulties arose from the want, for a long time, of proper roads and bridges in its vicinity. Pegg's Run, whose course was along what is now Willow Street, caused an extensive district of marsh and meadow as far north as the junction of Front Street and Germantown Road; and on the south, similar low lands reached to and even below Callowhill Street. Watson refers to this difficulty as follows:—

“The great mill, for its day, was the Governor’s Mill, a low structure on the location of the present [1830] Craige's factory. Great was the difficulty then of going to it, they having to traverse the morass of Cohoquinaque (since Pegg’s Run and marsh), on the northern bank of which the Indians were still hutted. Thence they had to wade through the Cohocsinc Creek beyond it. Wheel carriages were out of the question, but boats or canoes either ascended the Cohocsinc, then a navigable stream for such, or horses bore the grain or meal on their backs.” 2

Records exist of horses and their riders sinking and being lost in these marshes and quicksands, between Front and Third Streets. Watson again says (1: 478): “In the year 1713, the Grand Jury, upon an inspection of the state of the causeway and bridge over the Cohocsinc, on the road leading to the Governor's Mill, where is now [1830] Craige's manufactory, recommend that a tax of one pence per pound be laid to repair the road at the new bridge by the Governor’s Mill and for other purposes.”

Above Second Street, northwest from Germantown Road, and towards the mill pond, the land became considerably elevated; and, excepting the space between the creek and the mill-race, the locality was, even up to 1820, one of much sylvan beauty, sometimes made wild enough, however, when, after heavy rains, the widely swelled creek rushed along over its muddy bed like a mountain torrent. The banks and vicinity of the mill-pond were for many years a favorite resort. Miss Sarah Eve, whose interesting diary is published in PMHB (Vol. 5: 198), tells how she and a friend wandered around its shores and gathered wild flowers.